SUBMISSION TO THE NEW ZEALAND PRODUCTIVITY COMMISSION INTERNATIONAL FREIGHT TRANSPORT SERVICES

1. INTRODUCTION

1.1 The Shippers Council welcomes the opportunity to submit to the New Zealand Productivity Commission’s Issues Paper on International Freight Transport Services.

1.2 The efficiency, reliability and cost-effectiveness of our international supply chains is particularly important for an island nation such as New Zealand, because not only are we geographically distant from our key trading partners, with a small domestic population, our economic prosperity is totally dependent on the performance and international competitiveness of our export sector. If international freight costs are reduced then trade will be enhanced, the economy can be more productive and New Zealanders more prosperous.

1.3 According to Statistics New Zealand, approximately 99.6% of New Zealand’s trade volume in 2008 was carried by sea to/from overseas markets. The Shippers Council therefore thinks it appropriate for this issue to be one of the first considered by the Productivity Commission.

1.4 This submission will seek to answer the questions posed in the Issues Paper. We will also consider submitting on the Productivity Commission’s draft report which is due to be produced in December.

2. QUESTIONS

Q1. Are there important issues that may be overlooked as a result of adopting an economic efficiency perspective for this inquiry?

The Shippers Council supports the taking of an economic efficiency perspective for this inquiry for the reasons set out in section 2.2 of the Issues Paper noting that environmental considerations are also covered.

Q2. Is the framework described in section 3.2 appropriate for this inquiry? Are there any important issues that might be missed?

The Shippers Council supports the inquiry focusing on the three proposed efficiency perspectives (efficiency of individual components, efficiency at the interface between components, and efficiency of the whole logistics chain).Shippers take an end to end supply chain view and we are pleased that the inquiry is also covering this aspect.

Q3. Which components and component interfaces warrant greater attention? What is the evidence that they are inefficient? What contribution could changes make to an improvement of the overall efficiency of the freight system?

The Shippers Council agrees with the proposed emphasis on those areas where there is little or no effective competition.

We agree that domestic transport, particularly road transport, is competitive.

It is timely to look into the competitiveness of overseas shipping and whether the benefits of collaboration agreements exceed the costs. Stevedoring and ports merit particular attention as these are where it is most likely that gains can be made through policy and/or legislative changes.

The Shippers Council accepts that biosecurity and customs processes should be streamlined and costs should be reduced. However, New Zealand relies more than any other country on stringent biosecurity to safeguard export industries and the economy. We would strongly oppose any moves to weaken biosecurity standards and controls.

Q4. What environmental consideration should fall within the scope of the inquiry? What issues are of particular importance?

A reduction in the carbon profile of shipping is particularly important for New Zealand because:

Geographically, New Zealand is a long distance from many of its key international export markets. Accordingly, the transportation of New Zealand exports to overseas markets is more carbon intensive than goods that do not have to travel as far. This may affect the demand for New Zealand products in an increasingly environmentally savvy global society.

Any future international carbon trading or taxation scheme that covers the international ocean freight industry would increase shipping costs for exporters and importers. Whilst maritime greenhouse gas emissions are not yet covered internationally by the likes of the Kyoto Protocol, there is increasing pressure on the United Nation‟s International Maritime Organisation to introduce emissions tax or trading scheme for ocean freight (United Nations‟ Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific, 2007).

Given New Zealand‟s reliance on international shipping and our distance from key markets, at the current international carbon price of approximately €10 per tonne of carbon emitted, New Zealand exporters and importers would be particularly adversely impacted.

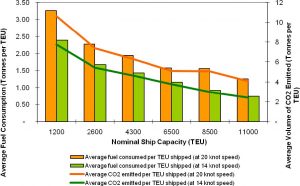

Larger ships are more fuel efficient (and therefore more carbon efficient) than smaller ships because less fuel is required to transport each TEU of cargo. An analysis of the fuel and carbon efficiency of various sized ships (shown in Figure 1) confirms that both the average amount of fuel consumed per TEU transported and the average volume of carbon emitted per TEU transported decreases with increasing ship capacity.

Figure 1: Average Fuel Consumption and Carbon Emissions per TEU for Various Sized Ships

Source: New Zealand Shippers‟ Council analysis

In addition to the design fuel efficiency of ships, there are also opportunities for shipping companies to increase fuel and carbon efficiency by sailing at lower speeds, and ensuring that the hull of the ship is smooth to reduce water resistance (Stopford, 2009).

A number of international shipping carriers have introduced slow steaming (reduced shipping speeds from around 20 knots to 14 knots) on a number of its routes in an effort to reduce bunker fuel consumption and carbon emissions. While carriers benefit, the increased shipping time to market as a result of slow steaming is unacceptable to exporters (particularly for exporters of highly time-sensitive perishable goods such as fresh fruit and vegetables, and chilled meat) without corresponding freight rate concessions to offset the additional transit time and wider supply chain costs incurred as a result (e.g. higher depreciation and inventory holding costs). In saying this however, even with freight rate concessions, significant increases in transit times will still not be acceptable to some exporters of perishable goods because of the finite shelf-life of some goods (e.g. chilled meat, and fresh fruit and vegetables).

The inquiry also needs to consider research which shows that New Zealand food products exported and sold in the UK and Europe are much less energy intensive than locally produced food, even when considering the long distances from export markets.

We also believe that the inquiry should consider the costs imposed on the supply chain by the Emissions Trading Scheme and impact of the ETS on New Zealand‟s international competitiveness given that most of our trading partners have no price on carbon and are unlikely to have such a price for the foreseeable future.

Q5. To what extent is there effective competition for customers between New Zealand ports? Has this led to lower prices and incentives for productivity improvements?

We believe that there is effective competition in the container trade but some bulk cargo is captured by particular port. Overseas shipping operators can and do swap port calls and their ability to gain price concessions from port companies to attract or retain business is an indication that there is some competition between ports. Central government commissioned a report in port performance and market power that was completed by Charles Rivers and Associates released in April 2002 that has a similar conclusion to the above.

Despite some competition between ports (and perhaps some price cuts) there does not appear to have been a pay-off in terms of improved productivity. Although data on port productivity is patchy, most New Zealand ports appear to have low productivity compared to overseas ports with some notable exceptions.

Q6. What are the most appropriate and reliable data available to measure port efficiency and productivity in container handling?

Q7. What are the most appropriate and reliable data available to measure port efficiency and productivity in handling bulk cargo?

There are many international measures for port performance that could be drawn upon. Closest to home, the Australian Department of Infrastructure and Transport‟s Waterline publication lists a large number of measures across landside performance indicators, stevedoring productivity, port interface cost index, ship visits, etc which would seem most appropriate. Whatever the measures chosen care must be taken to ensure there is an apples to apples comparison and definitions and formulae are the same for all. In comparison there is a real dearth of New Zealand information.

Q8. Which overseas ports are appropriate comparators for New Zealand port performance? On what basis should this selection be made?

New Zealand should aspire for its ports to be among the most productive. We should therefore benchmark our ports against the top performing ports.

In terms of geographical comparators we should focus on the ports of our major trading partners, particularly Australia.

Q9. Did port productivity improve during the 1990s? What were the drivers of those improvements?

There is a paucity of comparative data on port performance but The Shippers Council‟ understanding is that port productivity did improve in the 1990s. The main drivers of this improvement came from the corporatisation and part privatisation of ports and the reform of employment legislation.

The Port Companies Act 1988 corporatised the ports and required them to operate as successful businesses. Over the next few years a number of port companies‟ local government owners chose to partially privatise their holdings. This reform helped make ports more commercially-driven and more motivated to seek productivity improvements.

Changes to employment law were also very important. In 1989 the Waterfront Industry Commission (which had employed all waterside workers) was abolished and waterside workers became employed by the individual port companies. This was followed by the Employment Contracts Act 1991 which enabled significant changes in port workplace practices to be made.

Q10. Did the rate of productivity improvements flatten during the 2000s? Why? What might reinvigorate performance improvement?

There is a paucity of comparative data on port performance, but the Shippers Council‟ understanding is that port productivity did flatten during the 2000s. During the 2000s there was a trend of diminishing private sector investment in port companies (most evident in the removal of Ports of Auckland from the stock exchange and reversion to 100% local authority ownership). This has been coupled by what appears to have been a reduced appetite from port companies‟ local authority owners to demand significant efficiency and productivity gains. The reason for this lack of appetite is likely to be political rather than economic.

As a result, port companies seem prepared to concede a lower level of performance (and ultimately returns on their investments) in return for:

Keeping port operations in the council‟s geographic area (i.e., resisting rationalisation);

Strengthening or retaining local authority control (e.g., Ports of Auckland example above, and the abortive deal for Hong Kong based Hutchison Port Holdings to operate Lyttelton Port operations), or

Preserving industrial harmony

Containing capital investment levels to ensure a consistent dividend flow to council controlled entities to support general council spending

With regard to the point on industrial relations, the repeal of the Employment Contracts Act in 2000 and subsequent creeping changes to the Employment Relations Act are likely to have strengthened the hand of unions relative to the 1990s.

However, without more and better data on port performance across a range of productivity measures it is impossible to answer this question definitively.

Q11. What is the most appropriate way to measure port profitability? What is an appropriate rate of return on assets and equity?

As mentioned in the Issues Paper there is debate on how to measure port profitability and what rate of return to use. The Shippers Council is not in a good position to answer either of these questions definitively.

Any measure of port profitability should include with wider economic benefits to the region.

Q12. Is there evidence of a systemic problem of low port profitability? Or, conversely, excessive profitability?

The answer to this question depends on the answers to Q11 above. Settling on appropriate measures for port profitability is necessary before assessing if they have been inadequate , reasonable or excessive.

However the KPMG port performance reports from the early 2000‟s indicated low levels of port profitability

Q13. What levels of investment have ports undertaken in recent years? Are they consistent with accessible and efficient services to exporters and importers? Is there an over or an under investment problem in ports?

A figure of NZ$1billion invested in the last decade has been quoted by industry participants is small by world standards when compared to the $1b on dredging by Port Melbourne alone but ports will argue it‟s prudent. This question is the subject of debate with some saying that there has been overinvestment while others saying that investments in new capacity have been relatively modest.

As to whether there has been over or under investment there will be a different answer for each port but in total investments have been tracking growth. The issue is duplication of investments to attract customers.

Q14. Does New Zealand have too many ports for a small country? If so, what barriers are inhibiting rationalisation?

It is often said that NZ has too many ports for the size of the country but it is important to look beyond total population. By global standards we are overserved in container ports with approx. 1.2m teu throughput but consideration needs to be given the country‟s geography, topography, population distribution, the sources of exports, and the destination of imports.

There are likely to be a number of reasons why rationalisation has not happened. The most obvious is to do with ownership where all ports are majority owned by local government. They generally value the port in terms of economic benefits to the region rather than just the ports financial performance and hence are reluctant to give away any control, There is also a feeling that port owners seem unwilling to allow their ports to be „downgraded‟ through rationalisation especially where there is also a lack of effective alternatives to overseas ship calls due to cost and service shortcomings with coastal shipping and rail.

The physical barrier is vessel size, we are capped at circa 5,000TEU whilst ships up to 18,000TEU are in service.

Q15. Has local authority ownership of majority stakes in New Zealand’s commercial ports inhibited, enhanced, or been neutral for the development of a more efficient and productive port sector?

This has to be considered on a case by case basis. Some ports have had a good relationship with their owners and investments have produced greater efficiencies while others are not willing to fund future development.

What needs to be considered is the difficulty and cost associated with obtained resource consent to expand port capacity.

Q16. What changes in governance, regulations or ownership would offer the best means to improve port performance for exporters and importers?

The NZ Shippers Council believes that port companies should be encouraged to operate more commercially. We believe that this can be achieved by embarking on further port reform and changes to employment law.

With regard to port reform, we believe that local authorities should be encouraged to partially sell down their holdings in port companies, to at least the level of Port of Tauranga (55%). Partial privatisation should dilute the influence of parochialism and other political considerations and help make ports more commercially focused, while retaining majority local and public ownership.

Reforms could also be considered to encourage port companies to contract out port operations (i.e., the landlord port model) or enable competition for services such as stevedoring (as takes place at Port of Tauranga). Whatever is contemplated cannot be at the expense of increasing the scale and economies of scale that a small country like NZ needs.

Although the present government has made some modest changes to the Employment Relations Act there are still things that could be done to make the labour market more flexible and enable changes to work practices – for example, by ending the monopoly unions have on collective bargaining.

What we do not want is outsourcing to a private operator without labour reform. This could lead to increased costs but no increase in efficiency. Multiple (global) operators on a single terminal is not feasible given our low volumes.

Q17. How much variation in the efficiency and productivity performance of ports is explained by the way that within-port activities are organised? Do ‘contracting out’ and ‘landlord’ models offer a way to increase competition for the benefit of exporters and importers.

Considering that Port of Tauranga appears to be a significantly better performer than other New Zealand ports, the way within-port activities are organised could be a significant factor. The Shippers Council would support initiatives such as contracting out and landlord port models with the key point being fix labour model before you fix the operator/landlord model.

Q18. To what extent do inflexible labour practices and difficulties in employer-union relationships remain an obstacle to lifting efficiency and productivity at New Zealand ports?

Inflexible labour practices are often cited by port companies as an obstacle to improving productivity. Ports operate 24 hours a day and seven days a week and must have the ability to obtain labour as required rather than on fixed terms– refer to POAL failed efforts to get Bledisloe and Fergusson terminals to work together due to different collective agreements on the two terminals.

Q19. From the perspective of New Zealand importers and exporters, to what extent is the international shipping industry competitive?

International shipping is a competitive industry where there are several carriers or carrier groups on any trade route. Where this is not present competition diminishes and in rare circumstances a monopoly exists.

New Zealand has attracted many carriers in the past and benefited from sufficient capacity to enable goods to be received or exported but capacity has diminished in the previous two years as carriers have formed sharing arrangement.

Refer to cap on ship sixes which drives higher per slot costs for NZ services due to our 5,000teu limit versus 18,000teu that some of competitors enjoy.

Q20. To what extent have collaboration agreements between international sea carriers been helpful or harmful to the interests of New Zealand importers and exporters?

Collaboration agreements are necessary to guarantee levels of service to and from countries like New Zealand at reasonable cost. The problems for importers and exporters occur when price and capacity information is exchanged allows the opportunity for uncompetitive behaviour. It is likely that such behaviour has occurred but on balance collaboration agreements have probably been. Given that other countries are scrutinising and questioning such agreements it is timely and reasonable for New Zealand to do so.

Q21. What is the basis for the different regulatory treatment of imports and exports under the Commerce Act and Shipping Act? Is this differential treatment justified?

The Shippers Council is not aware of the reasoning behind separate frameworks

Q22. Have any actions (foreshadowed or actual) been undertaken under the Shipping Act 1987? Does the Act deter unfair practice?

The Shippers Council is unaware of any actions. The absence of actions might mean that there have been no unfair actions (which might mean the Act could be a deterrent) or it might be that the hurdle for „unfair actions‟ is too high (in which case the Act might not be a sufficient deterrent).

Q23. Would the Commerce Commission be better placed than the Minister of Transport to oversee the regulation of international shipping services?

The Commerce Commission is the logical agency for competition regulation. As well as its generic function it also regulates a number of specific industries including electricity, gas pipelines, airports, and telecommunications. Compared to the Ministry of Transport, the Commerce Commission might have more resources or expertise to devote to competition in international shipping. On the other hand, we have not seen the need for any specific interventions so the Ministry to be the responsible agency. Either way, it would be useful to consider this issue further.

Q24. To what extent do the current regulatory and competition regimes that affect international sea freight transport services work well or not for New Zealand exporters and importers?

As mentioned in the answer to Q20, a degree of collaboration between shipping companies is likely to have been necessary to ensure levels of service to and from New Zealand at reasonable cost. However, the Shippers Council is unsure whether the current regulatory and competition regimes have struck the right balance between competition and collaboration. We attach a view from the Director General for Competition of the European Union in his letter to the Competition Commission of Singapore when they were reviewing exemptions for liner shipping.

Q25. How do international shipping conferences permitted under the Shipping Act 1987 affect the accessibility and efficiency of sea freight services available to New Zealand exporters and importers? How strong or weak is the case for the exemption of conferences from the competition provisions of the Commerce Act?

A degree of collaboration between shipping companies is likely to have been necessary to ensure levels of service to and from New Zealand at reasonable cost. However, it would be useful to consider whether certain types of collaboration agreement (such as shipping conferences) are helpful or harmful methods of collaboration. Requiring registration and/or public release of agreements might be a useful step in preventing their misuse.

Q26. What lessons can New Zealand learn from the different ways that competition law and regulators in other jurisdictions deal with international sea freight services?

New Zealand should always seek to adopt best practice in regulation. That said, there will occasionally be issues specific to New Zealand that mean that what might work well in Europe, the US, or even Australia might not work as well here. With regard to international shipping, New Zealand‟s small share of world trade and its remoteness might mean that prohibiting collaboration agreements would compromise level of service and/or impose higher costs on exporters and importers. It is a tricky balancing act and one that needs careful consideration.

Q27-Q45

Questions 27 to 45 relate to airports and air services which the Shippers Council does not generally comment on. We therefore have no specific comment to make although our comments with relation to ports and shipping services might be relevant for airports and air services.

Q46. What are the typical customs and biosecurity costs faced by exporters and importers? How are these costs broken down? Is there scope to reduce them?

The main costs for agricultural importers and exporters within New Zealand take the form of such items as customs and excise charges, the issuing of phytosanitary e-certificates, ACVM charges, farm machinery importation charges, container inspection costs and personal goods inspection. The costs are administered by both the Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry (MAF) and Customs.

The development of the Joint Border Management System (JBMS) is seen as the main initiative to reduce import and export costs. A system that allows the sharing of processes, data and technology between MAF and Customs should create a more efficient lower-cost system, which is welcomed if properly implemented. As with any new system, it is important that consistency in meeting end goals is applied, as one of the reasons for increasing border clearance costs and the current cost under recovery is the inconsistent application of chargers from the government agencies.

Q47. Do New Zealand’s customs and biosecurity systems deliver the required outcomes efficiently? What initiatives might improve efficiency and effectiveness?

On an international basis the New Zealand border systems are rated highly but can be viewed as out dated, with some of the current computer clearance processes being in the vicinity of 10 to 15 years old. The outdated technology often results in slow goods clearance and places a greater emphasises on physical processes.

The JBMS will provide Customs and MAF with modern technology to:

receive and process enhanced electronic cargo and passenger information;

simplify and better manage border clearance processes for trade and travel;

target high-risk and facilitate low-risk people, goods, and craft;

enhance linkages to other government agency systems;

improve coordination of resources across agencies; and

contribute to improved logistics management in the supply chain

The JBMS is timely and any Government initiative aimed at reducing taxpayer funded administration costs without a loss in technical robustness or efficacy would be supported by The Shippers Council.

If, however, there is any risk of biosecurity slippage from the JBMS then The Shippers Council proposes that this is counteracted by affected agencies prior to the initiative being implemented. Biosecurity is a major concern to our members and any reduction or compromise to the current inspection regimes to save money or time would not be supported by The Shippers Council.

Q48. Does the World Bank analysis fit with the experience of importers and exporters? What opportunities are there to eliminate and/or streamline documents? Would this make a material difference in the total cost or speed of the logistics chain?

The Shippers Council concurs with the World Bank analysis and sees the JBMS implementation as the conduit to greater productivity.

Q49. Are there any measures that New Zealand could undertake to reduce the security-related costs imposed on exporters and importers?

Increased security related measures have by and large come from the US, then picked up by other jurisdictions. New Zealand needs to continue to foster close relations with the US as has been the case to ensure our exports stay in the „green lane”.

Exported goods from New Zealand are viewed generally as a low security risk, with MAF requirements providing a very high level of security. There is often duplication from Customs on exported goods and having smarter information sharing between agencies should assist in reducing compliance costs. This needs to be progressed.

From an importation point of view the Shippers Council remains opposed to a reduction in border security costs unless our clearance systems remain at a standard where there is no reduction to our current security measures. An imported freight item such as a shipping container poses considerable biosecurity risk to New Zealand and we are of the opinion that the importer of the container should be charged accordingly to reduce or annul any identified risks.

An importer is rarely prosecuted or fined when a biosecurity incursion occurs and in most cases the affected industry is wrongly left to cover the costs. As the importers are creating the risk then it is essential that they should cover the cost of that risk, even to the point of providing funding towards readiness and response activities.

Therefore, the Shippers Council proposes that instead of reducing charges to importers of sea containers and other imported products, charges should if anything be increased. This would enable MAF border inspection services to be enhanced (and paid for by the exacerbators), with any surplus funds used to cover any readiness or response costs associated with imported goods.

Q50. What transaction costs are associated with import tariffs? Are there administrative or other changes that could improve the efficiency of tariff collection?

The Shippers Council has advocated for reducing and removing tariffs on imported goods. Tariffs neither raise much money for government nor offer significant protection for industries.

The Shippers Council submits that New Zealand‟s remaining tariffs should be phased out to lower at-border costs and promote New Zealand‟s international connectedness. Unilateral elimination of tariffs would also show the world that New Zealand remains committed to free trade.

Q51. What changes in domestic transport institutions, policies and regulations might lead to the greatest improvements in the economic efficiency of the international logistics chain?

Road Transport

The Shippers Council agrees that road transport is a very competitive industry. We do not believe that any changes need to be made to road transport policy or regulation. However, we are concerned by funding

decisions that are being made that is reducing investment from the National Land Transport Fund into maintaining and upgrading local roads, especially those in rural areas.

While we support the new and increased investment in „Roads of National Significance‟ it is concerning that the recently adopted Government Policy Statement on Land Transport Funding signals a funding squeeze for local roads1. This squeeze will result in pressure on councils to increase rates and/or reduce levels of service, which could lead to deterioration in the roading network. Neglect of rural roads would not be in the interest of the international logistics chain given that most of our exports originate in rural areas.

The Shippers Council strongly believes that the entire roading network should be treated as a network and it should be funded accordingly. Local roads should be funded on a similar basis to state highways – i.e., by road users (via petrol taxes and road user charges) rather by property value based rates which bear no relationship to use of the roads. Unfortunately, the GPS signals a move in the opposite direction.

We are concerned that this squeeze on local roads will impact exporters ability to obtain heavy vehicle permits ie >44MT GWT as councils will be unable to deliver a complaint roading infrastructure.

Rail

The Shippers Council agrees that rail is a suitable transport mode for some freight, especially long-distance bulk goods. And the council notes rail‟s high share of container volumes to a number of ports, in particular Tauranga and Otago

However, we are concerned that rail investment is focussed on the passenger services which do not benefit the vast majority of importers and exporters as city workers tend to be service based and there is evidence that rail is not generating enough revenue to cover its costs and is heavily reliant on the taxpayer for capital grants and operating subsidies, and whilst we strongly suspect that these subsidies are related to the provision of passenger services there is a danger that high levels of subsidy prevents much needed investment in the freight network. While there may be a case for some government investment in rail infrastructure (at least in the short-term), rail services should operate without the need for operating subsidies. Policies and funding decisions that favour one mode over another should be avoided. It is important that road transport remains a highly competitive and cost-effective industry.

Coastal Shipping

As with rail, The Shippers Council agrees that coastal shipping is a suitable transport mode for some freight, especially long-distance bulk goods. As with the discussion above for rail transport, we believe that policies and funding decisions that favour coastal shipping should be avoided.

Q52. How competitive is the freight forwarding industry that serves New Zealand exporters and importers? Do the recent Commerce Commission investigations of a number of firms indicate that there are systemic problems, or that the regulatory and competition regime is working well?

The Commerce Commission has been undertaking enforcement action against various multi-national freight forwarders following a 2007 investigation around alleged collusion on freight forwarding services.

In a recent judgment the High Court found that there was a “sustained course of conduct involving covert meetings and communications”. So far, the Court has ordered a total of $8.85 million in penalties against several freight forwarders with a further case to come.

The fact that the conduct was investigated and successful enforcement actions pursued would indicate that the regulatory and competition regime is working as it was intended.

Q53. What are the costs of transit times for exporters and importers?

We refer you to section 3.4 of „The Question of Bigger Ships” report we published in 2010;

Value of Time

A number of recent international studies have examined the impact of the length of transport time on the cost of trade, and a country‟s overall trade performance. They find that lengthy shipping times impose additional costs on shippers and reduce the overall competitiveness of a country‟s exports.

Conversely, lower transport time reduce costs and have positive economic benefits for exporters, importers, and for the country as a whole. Transit times may be reduced if cargo is aggregated (e.g. by rail) to a bigger ship port in New Zealand, and then shipped directly to a major international transhipment port, rather than steaming around a number of New Zealand ports first.

Hummels (2001) identifies two time-related costs for exporters and importers. They are:

Inventory holding costs. For exporters, inventory holding costs include the opportunity cost of capital tied up in goods while it is in transit. For importers, inventory holding costs include the cost of having to hold larger stocks of inventory to accommodate for variations in the arrival time of imports. For imported goods, any additional inventory holding cost is likely to be inflationary, as importers pass on these costs to their customers. There is less scope for exporters to pass on these costs, as it would reduce the international competitiveness of New Zealand‟s exports.

Assuming a weighted average cost of capital of 10% per annum, inventory holding costs equate to approximately 0.03% of the value of the cargo per day.

Product loss of value. This captures any reason that a newly produced good might be preferable to an older good. Examples include the spoilage or reduced shelf life of fresh meat and produce, items with immediate information content (e.g. newspapers), and highly seasonal goods that are difficult to forecast demand (e.g. Christmas or Easter themed products, seasonal fashion apparel).

For the chilled meat and fresh produce sectors, that the rate of depreciation is exponential – i.e. the rate of depreciation (loss of value) is relatively low or non-existent initially, but increases quite steeply as transit time increases.

Related to this, changes to shipment time to market also has wider macroeconomic impacts on a country‟s overall trade performance if it reduces the export viability of fresh products.

For example, the Meat Industry Association noted that the shelf life of chilled meat ranges from 70 to 90 days. If transit delays mean that chilled meat has to be frozen down, its economic value could be reduced by up to 50%, as it is in essence a distressed product.

It is important to note that in cases where transit times are too high or there are uncertainties about shipping times, the export of fresh or chilled product is not a viable business model. Meat is therefore likely to be exported in frozen form (at a discount to chilled product) rather than in chilled form.

Q54. What sources of delay contribute to transit time? How might those delays be efficiently reduced?

Delays can occur at any point in the supply chain whether they come from man made reasons like congestion or acts of god like weather extremes. Slow steaming can delay transits and has already been discussed in Q4 In addition container transshipments add considerable time delays.

Q55. Are there potential efficiency gains from vertical integration in New Zealand’s international sea freight services? What are the disadvantages? What might need to change in order to allow or encourage greater vertical integration?

Q56. Are there potential efficiency gains from the vertical unbundling of specific components or activities in New Zealand’s international sea freight services? What are the disadvantages?

The Shippers Council believes that there would be efficiency gains from both vertical integration and vertical unbundling. Apart from a couple of isolated exceptions, innovations like vertical integration and unbundling of specific components and activities do not appear to have taken off in New Zealand. We agree with the suggestion in the Issues Paper that a factor behind this lack of uptake may be majority (and in many cases 100%) local authority ownership of ports infrastructure and government ownership of rail services.

As discussed in Q16, port companies need to be encouraged to operate more commercially. Increasing the levels of private investment in port companies should help dilute the political influence on decision-making and promote more commercially driven innovative solutions, such as vertical integration and vertical unbundling.

We should acknowledge the success of Metroport in driving the growth of the Port of Tauranga and is a good example of vertical integration.

Q57. Should decisions on investments in ports and in the associated infrastructure links to ports be left to the judgements of the individual suppliers of the separate components? Or would some sort of overall strategic plan provide useful guidance and some assurance that complementary investments will happen?

The Shippers Council believes that government direction should not be necessary for port investment decisions. Port investment decisions should be able to be left to individual port companies based on their commercial judgment and forecasts of demand. However there is scope for direction from central government similar to the Australian National Ports Strategy which addresses common concerns without impinging on commercial imperatives. Internationally, Governments are taking a lead role in their port and freight sectors to address significant risks and challenges, NZ is facing many of the same challenges and our government should set some guiding directions.

Investment in associated road and rail investment is provided by government agencies and a strategic plan for such infrastructure would make more sense. We would envisage such a plan being informed by port company investment intentions rather than it dictating investment to port companies.

Q58. What is the scope for greater consolidation of ports, greater vertical integration of ports with domestic transport operators, or more use of long-term agreements between shippers and port companies, as possible means to overcome coordination problems and achieve more efficient international supply chains?

Port merger discussions have been happening for some time in NZ but there has always been an insurmountable obstacle that defeats any arrangement. There is always scope but any form of consolidation needs to take account of the impacts beyond the regions the ports operate in. While a single merged entity could deliver improved asset utilisation and profitability for port shareholders, port mergers are of national importance clarity would be required with respect to:

What the purported synergies and benefits are and how they would be realised;

What the implications are for the wider supply chain;

How competitive pricing would be maintained in the absence of any real competition; and

The potential implications on continued investments given the reduced level of competition within the port sector

*greater vertical integration of ports with domestic transport operators?

NZ ports have been active in investing beyond the port gate and generally been successful. We can see advantages in this area.

* more use of long-term agreements between shippers and port companies?

Long term contracts are to be encouraged because they provide certainty for the parties involved.

Q59. Are there barriers to the negotiation of efficient agreements between ports and shipping lines?

The Shippers Council is not aware of any but you will have to ask the two parties involved.

Q60. Is there an asymmetry of bargaining power between ports and shipping lines? If so, what is the impact of this asymmetry? Are there any regulatory measures that might reduce the asymmetry?

Yes, it would appear that there might be asymmetry due to port companies being subject to the Commerce Act while shipping lines are exempt. We think it would be useful to consider whether this asymmetry is material and if so what can be done to reduce it. As discussed in Q20 and elsewhere we support an assessment being made of the impacts of international shipping collaboration agreements and shipping regulation generally.

Q61. Are the time costs associated with international air freight incorporated into current road infrastructure planning? To what extent should they be?

No comment.

Q62. Do domestic air links work as an effective feeder for international air freight services? What could be improved?

No comment.

Q63. Where in the logistics chain are time delays occurring, and how might they be addressed?

This differs from time to time and industry to industry.

Q64. Does the imbalance of container use create significant costs? What practical measures might efficiently reduce these costs?

There is little information on the costs of the container imbalance but they must be significant given its scale and the fact that empty containers need to be moved around the country to the regional export-oriented ports. The high seasonality of export trade is also an important factor.

However, the container imbalance is a fact of life given the nature of New Zealand‟s exports and imports, while the need to move so many containers around the country reflects number and location of New Zealand ports which in turn reflects the origin of exports and the destination of imports. New Zealand‟s container imbalance is not unique – other countries have imbalances some greater than ours. Lessons need to be learnt from an analysis of their supply chains .

Commercial solutions are more likely to reduce costs associated with the imbalance. As previously discussed in this submission innovative practices like vertical integration and vertical unbundling have been slow to be taken up in New Zealand. More private investment in port and other infrastructure should provide greater incentives to operate in a commercial manner and adopt innovative solutions.

Q65. What are the potential benefits and risks for New Zealand from a move to hub-and-spoke configurations for international shipping? Are there actions New Zealand can take to increase the likelihood of benefits or to manage the risks?

Hub-and-spoke configurations will be driven by the trend towards ever bigger ships and drives for efficiency. Hub-and-spoke configurations should enable lower voyage operating costs as a result of the economies of scale that bigger ships deliver. Lower operating costs Reduce the total cost of the supply chain so it can be expected that cargo owner would enjoy benefits.

Costs of hub-and-spoke configurations include potential increases in the internal transport costs if cargo has to be redirected to a smaller number of ports handling bigger ships. There is also likely to be an increase in port and other infrastructure costs to recover costs of investment required.

With ever larger ships coming into service, hub-and-spoke configurations seem inevitable. The key question is whether New Zealand develops hub ports or whether shipping companies prefer to hub through Australia. New Zealand ports need to lift their performance above those of Australia and as mentioned earlier in this submission this requires further reform of port ownership and practices.

Q66. To what extent do formal and informal alliances between airlines improve or detract from the efficiency of international air freight services? Are there opportunities to improve outcomes?

No comment.

Q67. What measures might improve the overall system efficiency of the logistics chain for international air freight?

No comment. .

Q68. Are import and export opportunities excluded or constrained by the lack of access to international freight transport services? Are there changes in institutions, policies or regulations that could lead to better outcomes?

NZ exporters have suffered from lack of shipping capacity in the recent past which has constrained opportunities. Carriers introduce and withdraw capacity continually and sometimes with little notice. We believe there is room for policy or regulation to gain greater forward visibility of service amendments.

Q69. Is there scope for increased sharing of operational data between transport firms to achieve improved coordination and efficiency? How might this be achieved?

Yes but as the Issues Paper suggests there are a number of complex issues that need to be resolved (such as data ownership and potential for misuse and stifling of competition. The Trade Single Window and JBMS system is considering a portal and we support development of this.

Q70. Do the restrictive trade practices provisions of the Commerce Act deter the efficient sharing of operational data?

This should be looked into, including how other countries deal with concerns about anti-competitive practices.

Q71. Is there a role for government to require the disclosure of performance measures in specific components, and to collate and publish that data?

Yes. It would be useful to have better information on port performance, for example, similar to that available in Australia.

Q72. Given likely future trends in trading patterns and transport technology, will the reliability, speed and efficiency of international logistics services be adequate for New Zealand’s interests? If not, what can be done to leverage opportunities and mitigate risks?

The more pertinent question might be whether New Zealand is able to take advantage of future trends in international logistics.

Q73. What is the best way to achieve efficient decisions and coordination for the large, lumpy and interdependent investments that typically occur along international freight supply chains?

The best way to achieve efficient decision-making is to encourage all players operate in a truly commercial and competitive environment. Investment and other decisions would then be best left to these players. The most useful thing any government could do is remove and reduce any barriers to implementing these decisions and ensure that its decisions around funding its roading and rail infrastructure is responsive the needs of ports, shipping lines, and shippers.

Ordinarily a national strategy would accommodate such investments but if this is not possible at least some guiding principles should be made public.

Q74. What factors would favour the choice of decentralised vs. centralised strategic planning?

There is room for both approaches. The Shippers Council prefers that suppliers of the individual components should be encouraged to make individual decisions relying on market forces to achieve efficient and coherent outcomes. For this to work the individual suppliers need to be operating on a fully commercial basis and be making decisions on commercial as opposed to political considerations. As previously discussed this requires further reforms of port ownership and practices.

There are aspects of investment (such as roading and rail infrastructure) where government is the provider and for them some centralised planning is necessary. However, as discussed above such planning should be informed by the needs of ports, shipping lines, and shippers rather than it dictating investment to these players.

Q75. What costs exist in the various components of the international freight transport supply chain and how have they been changing over time? How do these figures compare with those for other relevant comparator countries?

Supply chain costs vary significantly because of the variables involved. At the Shippers Council level we do not have such detailed information.

Q76. What productivity levels exist in the various components of the international freight transport supply chain and how have they been changing over time? How do these figures compare with those for other relevant comparator countries?

As discussed previously in this submission The Shippers Council submits that after making good progress in the 1990s productivity growth has flattened in the 2000s. This appears to be true both for the ports and the wider economy.

Q77. Are you able to contribute data that would assist the Commission?

Possibly. Our members may assist if contacted directly.

Q78. Has this issues paper covered the key issues? What other questions need to be asked?

Yes, we think the Issues Paper is very comprehensive.

Q79. What are the most important issues for the Commission to focus on to achieve the greatest improvements in the efficiency and productivity of New Zealand’s international freight transport services?

The Shippers Council believes that international shipping regulation followed by ports and associated activities such as stevedoring should be the highest priority, and customs and biosecurity costs.

3. ABOUT THE NEW ZEALAND SHIPPERS COUNCIL

3.1 The New Zealand Shippers’ Council is an association of major cargo owners (importers and exporters) in New Zealand.

3.2 The current membership of the Council includes companies and organisations with major interest in industries such as forestry, wood products, fruit, steel, dairy, meat and pulp and paper. Collectively the Council accounts for over 50% of New Zealand’s total exports by volume annually.

3.3 The objectives of the New Zealand Shippers’ Council are:

To be the national body representing large volume cargo owners;

To be the pre-eminent group in supply chain developments particularly relating to cargo handling and movement, commerce and legislation;

To be a major driver in supply chain and logistics training policy; and